The following is a review of an excerpt from a book titled Commentaries on the Constitution by Joseph Story, Boston, 1833. This text was written as part of a volunteer audio visual presentation featuring Thomas Paine for Patriot Lessons TV, recorded in 2015.

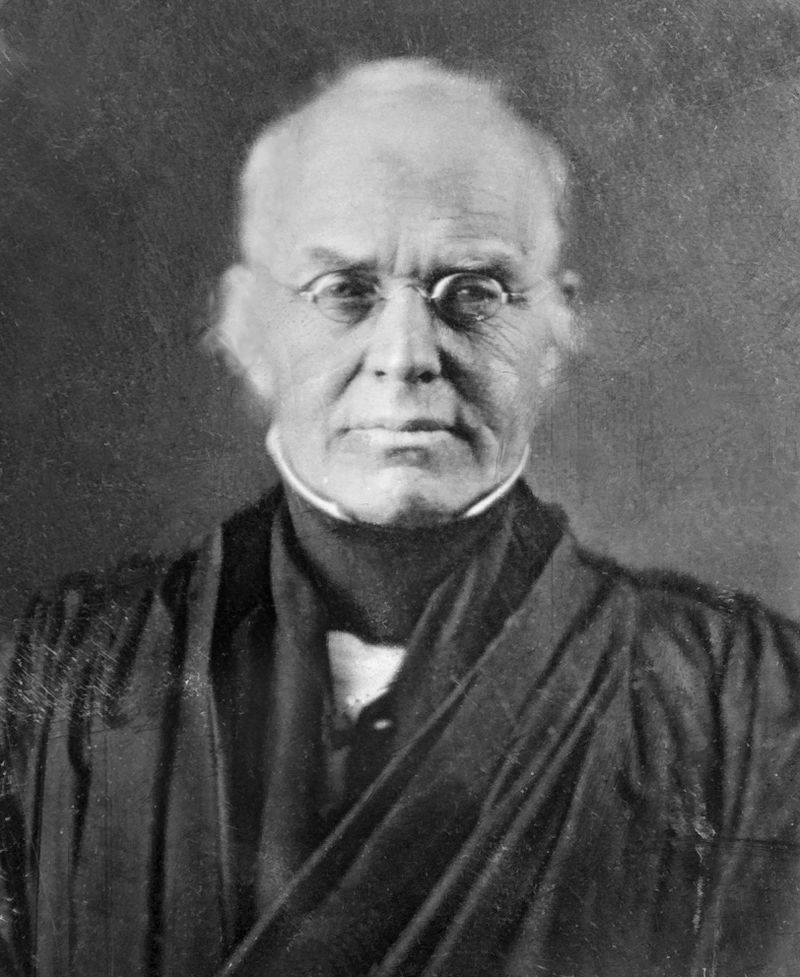

My name is Gregory Roth. I am a practicing probate and estates attorney in Novi, Michigan. I have had the opportunity to review an excerpt in the book, Commentaries on the Constitution of the United States, a three-volume work written by Joseph Story, Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States in the 19th century. Justice Story was fellow justice and friend of Chief Justice John Marshall. In the excerpt from these Commentaries, published in 1833, Story discusses the Full Faith and Credit Clause in Article IV, Section 1 of the United States Constitution.

The Full Faith and Credit Clause reads as follows: Full Faith and Credit shall be given in each State to the public Acts, Records, and judicial Proceedings of every other State. And the Congress may by general Laws prescribe the Manner in which such Acts, Records and Proceedings shall be proved, and the Effect thereof. Basically, the Clause provides that each State must recognize the legislative acts, public records, and judicial decisions of the other States within the United States. Story focuses on judicial decisions, or judgments, in this excerpt.

Story starts by explaining that the Constitution’s predecessor, the Articles of Confederation, contained a similar provision. The Clause also went through changes from the first draft of the Constitution.

Story then discusses the general rule of common law, in both England and America, that foreign judgments are prima facie evidence of the right and matter which they purport to decide. As prima facie evidence however, the authority and correctness of such judgments was still subject to attack. That is, the presumption that foreign judgments were valid could always be challenged.

Story writes that before the American Revolution, as much as the colonies were considered foreign to Britain, the mother country, they were also foreign to each other. Therefore, according to the common law, judgments of one colony were re-examinable in another colony, meaning that the jurisdiction of the foreign colony’s court and the merits of the matter decided could be questioned and even overturned. This created the possibility of obtaining a judicial decision in one colony and having it disregarded by another. This would lead to questions of law and matters of fact repeatedly open to litigation every time the parties sought out a new jurisdiction, or State. Matters could be re-tried at distances far from the location of the original dispute, after witnesses had died, or after much time had passed – thereby hampering a true understanding of the case. Story argues that while occasionally there could be a compelling reason for re-examining a matter, the evils of re-examining judgments of other States in every case would outweigh any benefit from finding a better resolution or correctness in a few cases.

In defense of the Full Faith and Credit Clause, Story writes that it was less likely that the States would deal less favorably with each other than they would with foreign nations. First, Story argues “necessity”: the States were united in a permanent bond with each other – i.e. a state was not allowed to secede from the Union under the new Constitution. Second, Story argues “opportunity”: based upon their natural proximity to each other, the commercial contacts of the States with each other would be constant and diversified. Under the new system of government, it was better to liken the judgment of a neighbor State to a domestic judgment than a foreign judgment of a separate nation. In Story’s way of thinking, Virginia was more like New York than it could ever be to England or France.

Story believes that the Full Faith and Credit Clause was the solution by the new American country to provide conclusiveness of judgments from any one State and to therefore promote uniformity and certainty among the colonies. As such, the Full Faith and Credit Clause was just one attempt by the drafters “to form a more perfect Union” and to give the States a higher security and confidence in each other. HN