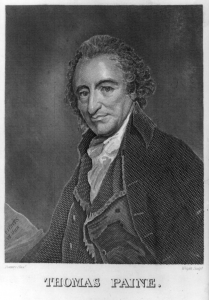

A review of a chapter title A World of Paine, in the book, Revolutionary Founders: Rebels, Radicals, and Reformers in the Making of the Nation by various authors, published in 2011. This text was written as part of a volunteer audio visual presentation featuring Thomas Paine for Patriot Lessons TV, recorded in 2015.

Revolutionary Founders is book of twenty-two original essays profiling an equal number of revolutionary individuals, both men and women, but most not so well-known to the general public. The book focuses on individuals whom it claims idealized the common person’s meaning of liberty and equality. Among those profiled is an Englishman named Thomas Paine who immigrated to America in 1774.

Paine is most known as the author of Common Sense, a famous forty-six page pamphlet that would help to convince the American people of the need of political separation from Great Britain. The chapter, titled A World of Paine, provides a summary of Paine’s contributions to revolution in general, not just the American Revolution, which earned him mixed blessings in American history.

Paine never achieved the status of the well-known Founding Fathers. The author calls him a “lesser founder” comparing Paine to Washington and Jefferson as one would compare superhero Aquaman to Superman or Batman; in essence, Paine was a like second tier superhero: only called upon when needed but never fully appreciated.

The author points out that Paine was the “poorest” of the Founding Fathers. Even so, Paine donated his share of the profits of Common Sense to buy supplies for the Continental army in which he also served.

Still, Paine’s chief contribution to the Revolution was writing a series of essays known as The American Crisis. The first were written by campfire light during Washington’s retreat across New Jersey in 1776 later to be read to the exhausted, frostbitten troops prior to Washington’s surprise attack on Trenton on Christmas Eve of that year.

Paine’s pamphlet, Common Sense, garnered much praise, yet to some, like John Adams, it was considered “tolerable” to “worthless”. Adams continued in his late years to call it “malicious” and “short sighted”. The author notes that Common Sense could not have been attributed to anyone but Paine.

Paine wrote for “everyone”, such that Adams complained that “History is to ascribe the revolution to Thomas Paine.” Yet, Paine himself turned down a request from Congress to write an official history of the American Revolution. Its eventual author, Mercy Otis Warren, ironically then relegated Paine to a literal footnote in her book.

Paine returned to England 1787. There he wrote the Rights of Man, a work he considered to be an English version of Common Sense. The first part sold fifty thousand copies in just three months; the second part was outsold only by the Bible. While there he also defended the French Revolution from English critics.

Paine’s continued stance against monarchy earned him both detractors and persecution, including smear campaigns against him. Paine fled to Paris in 1792. As the French Revolution raged, he wrote the first part of the The Age of Reason, challenging institutionalized religion. Paine was arrested and wrote most of the second part from a prison cell from which he saw fellow inmates go daily to their deaths. The U.S. government failed to secure his release. Paine was freed by his captors ten months later and returned to America in 1802.

Paine’s stances against organized religion politically isolated him. He lived his last years in New York and would never fully recover from diseases contracted in prison. As an old man, Paine tried to vote in a local election and was told that he was not an American citizen and was turned away.

Paine died in 1809, and by then all of the surviving Founders had renounced him. The book states that Paine “left little behind in his own defense”. His papers including an autobiography were destroyed in a fire, and even his bones were stolen and presumably destroyed.

A World of Paine highlights a man considered to be an organic revolutionary, both in triumph and in tragedy: a man whom American history has both admired and rejected. HN